Montana's colorful history includes the stories told through geology. Since 2006, the Montana Department of Transportation has installed nearly 50 roadside geological markers.

Each interpretive sign describes the geologic and paleontological wonders of the Treasure State to help share Montana's story.

![]() Click on the symbols below for details on Montana's unique landmarks:

Click on the symbols below for details on Montana's unique landmarks:

1. Kootenai Falls and the Belt Supergroup

Mile Post 21 on US Highway 2, west of Libby

GPS Latitude: 48.4529 Longitude: -115.7695

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The canyon along the Kootenai River exposes rocks of the Belt Supergroup, which consists of sandstones, called quartzites, and thin layers of hard mudstones or shales. These rocks form most of the outcrops along the highway from east of Libby to the Idaho border. In this area, the rocks are slightly folded so that the river cascades over the inclined hard quartzite beds in the stair-step-like falls. Individual folds may be seen in the north-facing road cut just south of Highway 2, southwest of the parking lot. Another fold may be seen north of the river. These folds resulted from east-west tectonic compression that caused north-to-south trending folds and faults throughout western Montana about 50 to 100 million years ago.

When the rocks belonging to the Belt Supergroup were deposited about 1.5 billion years ago during the Precambrian Era, much of western Montana was covered by shallow seas or lakes surrounded by very flat shores. Sediments in the water deposited thin beds of sand, mud, and calcium carbonate. The surfaces of the rocks often display mud cracks, ripple marks, and the spatter marks of raindrops. These structures can be found in outcrops along the Kootenai River, and indicate that the water covering the area was shallow, and occasionally, completely dried up. Algae mats often trapped fine particles of calcium carbonate to form rounded structures called stromatolites. Near the river below Swinging Bridge are wonderful examples of stromatolites.

Belt rocks dominate the mountains of northwestern Montana. The rocks along US Highway 2 between the Idaho border and the Continental Divide south of Glacier National Park consist almost entirely of the Belt Supergroup. The rocks next to the highway are brown, gray, red, green, purple, and yellow colors; dramatic cliffs occur where resistant, well-cemented sandstones are exposed.

2. The Rocky Mountain Trench

Montana Highway 37, MP 65

GPS Latitude: 48.9055 Longitude: -115.0999

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Eureka is situated in a 1000-mile long valley called the Rocky Mountain Trench. This gigantic rift valley stretches all the way from the British Columbia-Yukon border south to the St. Ignatius area and averages about 15-miles wide. The high mountains on both sides of the trench are composed of Precambrian sedimentary rocks that were deposited in an inland sea more than 1.4 billion years ago. But the mountains themselves did not begin forming until about 110 million years ago when the North American tectonic plate overrode the Pacific plate far to the west. This collision shoved enormous pieces of the earth’s crust eastward, where they rode up and over the rocks to the east along thrust faults and stacked up "like shingles on a roof" to create the Rocky Mountains. Then about 55 million years ago, the tectonic setting changed and the earth’s crust in this region began to pull apart, reversing the movement on some of the "shingles" and dropping them back down along normal faults.

The rounded hills along the highway north of Eureka are called drumlins. The elongated hills consist of glacial till that form near the lower ends of glaciers where the ice is thin. The hills are oriented parallel to the movement of the ice with the higher blunt end facing into the glacial movement and the thin tails trailing off in the downflow direction. Drumlins are whale-shaped in profile and like schools of monstrous tadpoles from the air. The hills usually occur in groups called a drumlin field.

3. Landslide Butte

Montana Secondary 213, MP 39

GPS Latitude: 48.9975 Longitude: -112.7886

In 1912 Smithsonian geologist Eugene Stebinger and paleontologist Charles Gilmore came to Blackfeet Country looking for dinosaur remains. Their search took them to a badland area near Landslide Butte, a prominent landform near the Milk River to the east of here. Stebinger named the sandstone and mudstone rock unit the Two Medicine Formation, and determined that it was nearly 2000 feet thick, representing a geological time span from 74 to 80 million years ago. From this formation, Gilmore collected and named 3 new species of dinosaurs. A second paleontological group from the Museum of the Rockies here in Montana, led by Jack Horner, explored this same area from 1985 through 1987, and discovered an additional 4 new species of dinosaurs, including one of the largest dinosaur nesting grounds on earth, covering nearly 6 square miles. In addition, enormous bone beds of duck-billed dinosaurs and horned dinosaurs supported theories that these kinds of dinosaurs traveled in gigantic herds, and may have migrated along the eastern front of the ancient Rocky Mountains. Three of the dinosaurs, known exclusively from this one area, are the horned dinosaurs Rubeosaurus, Einiosaurus, and Achelousaurus, hypothesized to represent an evolutionary sequence of transitional species.

4. The Lewis Overthrust Fault

US Highway 2, MP 198 Summit rest area

GPS Latitude: 48.3177 Longitude: -113.3531

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Although Marias Pass was well-known to Montana's Indians, it was a recent discovery by non-Indians. The Salish, Kootenai, and Blackfeet frequently crossed the pass to hunt buffalo and raid their neighbors. By the 1830s, the area had become so associated with the Blackfeet, that few non-Indians dared search for the pass. Isaac Stevens' railroad survey attempted to "discover" the pass in 1854, but failed to find it. In 1889, the Great Northern Railway sent engineer John F. Stevens to locate the pass. Stevens plowed through four feet of snow in subzero weather in search of the 5,214-foot pass, finding it on December 10, 1889. The Great Northern built its line over Marias Pass in 1891. It was not until 1930 that a highway was constructed over it. Before then, motorists on U.S. Highway 2 had to load their automobiles onto railroad cars at East or West Glacier to ship them around the southern boundary of Glacier National Park on the Great Northern. The railroad dedicated the statue of John F. Stevens in 1925. The federal Bureau of Public Roads installed the stone obelisk in 1930 after it completed the highway.

Although Marias Pass was well-known to Montana's Indians, it was a recent discovery by non-Indians. The Salish, Kootenai, and Blackfeet frequently crossed the pass to hunt buffalo and raid their neighbors. By the 1830s, the area had become so associated with the Blackfeet, that few non-Indians dared search for the pass. Isaac Stevens' railroad survey attempted to "discover" the pass in 1854, but failed to find it. In 1889, the Great Northern Railway sent engineer John F. Stevens to locate the pass. Stevens plowed through four feet of snow in subzero weather in search of the 5,214-foot pass, finding it on December 10, 1889. The Great Northern built its line over Marias Pass in 1891. It was not until 1930 that a highway was constructed over it. Before then, motorists on U.S. Highway 2 had to load their automobiles onto railroad cars at East or West Glacier to ship them around the southern boundary of Glacier National Park on the Great Northern. The railroad dedicated the statue of John F. Stevens in 1925. The federal Bureau of Public Roads installed the stone obelisk in 1930 after it completed the highway.

5. The Beaver’s Dam: Flathead Lake

US Highway 93, MP 57

GPS Latitude: 47.66172 Longitude: -114.1074

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

About 15,000 years ago, a glacier pushed its way down the Rocky Mountain Trench into northern Montana. At the northern end of the Mission Mountains, the glacier broke into two branches. One branch scraped down the west side of the range until it reached this place, where it stopped and began to melt, leaving behind this gravel-laden hill, called a terminal moraine. The ice remaining north of this moraine eventually melted away, creating Flathead Lake, the largest freshwater lake in the western United States.

In the Salish language, this hill is called Sqlew̓ Stqeps -- the Beaver's Dam. The name comes from a Pend d'Oreille creation story about White Beaver, a monster whose lodge was Wild Horse Island. The Wolf Brothers killed White Beaver, broke up his lodge, and breached the dam. The waters rushed out, leaving behind Flathead Lake.

This is one of many Salish and Pend d'Oreille creation stories bearing uncanny parallels with the geologic record of the last ice age. Other legends describe giant beaver and giant bison, great dams blocking the rivers, and the retreat of the bitter cold weather and establishment of the climate we know today. In these stories we can glimpse the collective memory of the most ancient reaches of the tribal past. Archaeologists have documented sites within Salish-Pend d'Oreille aboriginal territories dating back about 10,000 years, and say it is almost certain that people occupied the area at an even earlier time. These are the traces of the x̣͏ʷl̓čmusšn -- the ancestors -- who first occupied the region after Coyote and others rid the land of the naɫisqélix͏ʷtn -- the people-eaters.

The Pend d'Oreille band that lived in the Flathead Lake area was known in Salish as the Sɫq̓tk͏ʷmsčin̓t -- the People of the Broad Water, after the name of the lake, Čɫq̓étk͏ʷ, meaning Broad Water. The ethnographer James Teit wrote that the lake was "the earliest recognized main seat of the Pend d'Oreilles." Anthropologist Carling Malouf wrote that "the density of occupation sites around Flathead Lake, and along the Flathead River...indicates that this was, perhaps, the most important center of ancient life in Montana west of the Continental Divide."

6. A Lost World: Precambrian Belt Rocks

I-90, MP 4, Dena Mora rest area

GPS Latitude: 47.4193 Longitude: -115.6287 (east-bound)

Latitude: 47.4198 Longitude: -115.6255 (west-bound)

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Imagine a world very different than we know today. About 1.5 billion years ago during the Precambrian Era, the earth's environment was desolate, with no trees, fish, animals or birds. Shallow seas with extensive near-shore flats were fed by streams that deposited great amounts of sand and mud. Rain frequently fell and pooled in vast shallow lakes and ponds in what would one day become northwest Montana.

Imagine a world very different than we know today. About 1.5 billion years ago during the Precambrian Era, the earth's environment was desolate, with no trees, fish, animals or birds. Shallow seas with extensive near-shore flats were fed by streams that deposited great amounts of sand and mud. Rain frequently fell and pooled in vast shallow lakes and ponds in what would one day become northwest Montana.

Despite the hostile environment, blue-green algae mats often trapped fine particles of calcium carbonate to form structures called stromatolites, that grew in shallow nearshore environments. The surface of the rocks often display mud cracks, ripple marks, and, sometimes, the spatter marks of primeval raindrops.

The earth's crust slowly sank for about 100 million years forming a large geologic basin in which Belt Supergroup sediments accumulated as much as 10 miles thick! The rocks are common in northern and central Idaho and western Montana, and extend east to the Little Belt Mountains in central Montana. The sedimentary rocks along Interstate 90 between Lookout Pass and Alberton are almost entirely rocks of the Belt Supergroup. These rocks are distinguished by brown, gray, red, green, purple, and yellow colors and locally form dramatic cliffs where resistant, well-cemented sandstones are exposed in the canyon.

Interstate 90 from near Lookout Pass through Missoula is located along the Lewis and Clark Fault Zone, a series of faults that stretch between northwest Washington State and the Helena area. The faults had significant movement about 70 million years ago when the Rocky Mountains were uplifting and were active until at least 25 million years ago. Interstate 90 and US Highway 10 in western Montana follow the trend of the faults along straight canyons that eroded along the fault zone.

7. Glacial Lake Missoula

I-90, MP 72 (east-bound)/MP 73 (west-bound), Alberton parking area

GPS Latitude: 47.0126 Longitude: -114.5429 (east-bound)

Latitude: 47.0210 Longitude: -114.5200 (west-bound)

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

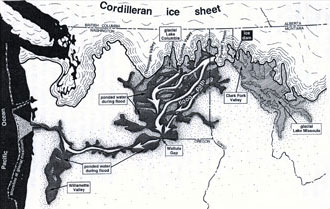

During the last ice age about 15,000 years ago, an enormous glacier pushed down from British Columbia and blocked the Clark Fork River in northern Idaho. The glacier functioned as an ice dam creating the largest glacial lake known to have existed, Glacial Lake Missoula. The lake's waters backed up into the river's drainage in western Montana, creating a body of water comparable to today's Lake Ontario. As the lake filled and water at the ice dam deepened, it caused the lighter glacial ice to float and eventually break up, triggering floods of epic proportions. The water flushed through the Clark Fork drainage west of here enroute to the Pacific Ocean. The torrent scarred the landscape of eastern Washington, creating scablands that still define the landscape. The geologic record indicates that Glacial Lake Missoula filled and emptied on a cyclical basis over a period of about two thousand years. Indeed, the large road cut where the Interstate 90 bridge crosses the Clark Fork River at Nine Mile, ten miles east of here, preserves the record of at least 36 separate fillings of the lake. Other evidence of the glacial floods include ancient ice age shorelines on the mountains around Missoula.

During the last ice age about 15,000 years ago, an enormous glacier pushed down from British Columbia and blocked the Clark Fork River in northern Idaho. The glacier functioned as an ice dam creating the largest glacial lake known to have existed, Glacial Lake Missoula. The lake's waters backed up into the river's drainage in western Montana, creating a body of water comparable to today's Lake Ontario. As the lake filled and water at the ice dam deepened, it caused the lighter glacial ice to float and eventually break up, triggering floods of epic proportions. The water flushed through the Clark Fork drainage west of here enroute to the Pacific Ocean. The torrent scarred the landscape of eastern Washington, creating scablands that still define the landscape. The geologic record indicates that Glacial Lake Missoula filled and emptied on a cyclical basis over a period of about two thousand years. Indeed, the large road cut where the Interstate 90 bridge crosses the Clark Fork River at Nine Mile, ten miles east of here, preserves the record of at least 36 separate fillings of the lake. Other evidence of the glacial floods include ancient ice age shorelines on the mountains around Missoula.

A Brief History: In 1860, 150 men under the command of Lieutenant John Mullan carved a wagon road through the colorful Precambrian mudstones on the mountainside north of here. The road took six weeks to construct and required the use of explosives to blast a route through the rocks. Called the Point of Rocks Segment of the Mullan Road, the road still traces its way across the mountainside above here. In 1908, the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific (Milwaukee Road) Railroad constructed its transcontinental line through the Clark Fork canyon enroute to Seattle. The railroad also excavated tons of rock to cut its way through these mountains to St. Paul Pass. The old railroad grade, later known as the Route of the Hiawatha for the celebrated passenger train that once used the line, is still evident along the north side of Interstate 90. In 1914, the Yellowstone Trail, blazed by distinctive chrome yellow signs with black arrows, passed through this canyon. The trail became U.S. Highway 10 in 1926. Interstate 90 bypassed it here in 1963.

8. Mountains on the Move: The Bitterroot and Sapphire Mountains

US Highway 93, MP 13

GPS Latitude: 45.8363 Longitude: -113.9811

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The spectacular Bitterroot Mountains northwest of Sula expose granite rocks of the Idaho batholith, a major geologic feature that consists of a series of igneous intrusions that pushed their way toward the surface between about 80 and 53 million years ago. The molten magma that formed these intrusions forced its way into older rocks and crystallized more than ten miles below the surface. As the magma rose upward, it raised up the overlying rocks, which sloughed off an enormous block that slid to the east, forming the Sapphire Range on the east side of the Bitterroot Valley. It took about seven million years for this block to slowly slide along a surface that forms the eastern slope of much of the Bitterroot Range. The granite rock exposed along US Highway 93 in the Sula area are part of this block that was once in the present Bitterroot Range. About 50 million years ago, magma again rose up through the crust of the earth resulting in the eruption of large volumes of volcanic rock in the southern Bitterroot Range southwest of Sula.

Glaciers capped much of the Bitterroot Range and carved dramatic U-shaped profiles into side drainages that flow eastward into the Bitterroot Valley. The last glaciation ended about 15,000 years ago. Multiple times during the glacial ages, a glacier dammed the Clark Fork River near the Idaho/Montana border forming Glacial Lake Missoula. The highest lake stand reached an altitude of 4,200 feet above sea level, forming a lakeshore only a few miles downstream of Sula.

9. Souvenirs of the Ice Ages

Montana Highway 200, MP 32, Clearwater Junction rest area

GPS Latitude: 47.0023 Longitude: -113.3690

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Highway 200 near this rest area passes through one of the most spectacular ice-age landscapes in Montana. Glaciers advanced out of the Mission and Swan ranges, and the mountains in the Bob Marshall-Scapegoat wildernesses, forming an ice cap that nearly filled in the valleys to the peaks from Salmon Lake to the Flathead Valley, about eighty miles north of here. Glaciers sculpted the rugged mountain peaks of the mountain ranges you can see from the rest area. This ice cap was connected to the vast Cordilleran Ice Sheet that extended into the United States from the Canadian Rockies.

Glaciers formed in this area multiple times over about 300,000 years during two ice ages: the Bull Lake and Pinedale. During the Bull Lake Ice Age, about 140,000 years ago, the glaciers flowed farther south into the valleys south of Ovando and Helmville. Between 60,000 and 15,000 years ago the ice cap formed again. Southward spreading glaciers carried gravel and sand into the Ovando area, about one to two miles south of Highway 200. Melting glaciers left behind mounds of rock and soil debris, called moraines. The low areas between the moraines mark places where the glacial till wasn’t deposited, leaving hollows that filled with water. Many of the ancient hollows can still be seen today as wetlands, shallow ponds and small lakes. Large depressions north of the rest area along Highway 83 are called kettles. Masses of ice buried in the outwash gravels melted forming the depressions.

The smooth broad plains to the north and east of here are glacial outwash plains. They were once the location of raging streams that carried meltwater loaded with mud, sand, gravel from the front of melting glaciers. These valleys are now the agricultural land along the Clearwater and Blackfoot rivers.

10. Madison Limestone and the Garnet Range

I-90, MP 143 (east-bound), Bearmouth rest area

GPS Latitude: 46.7037 Longitude: -113.3382 (east-bound)

I-90 Frontage Road (old US 10), MP 10, ten miles west of Drummond

GPS Latitude: 46.7204 Longitude: -113.3163

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

About 350 million years ago, much of Montana was submerged under a shallow sea. Billions of tiny marine creatures thrived in the water and when they died their bodies settled into the muck on the sea bed. After hundreds of millions of years of accumulation and many more millions of years it metamorphosed into the pale gray rocks that are known today as Madison Limestone. The limestone is common throughout Montana, eastern Idaho, northern Wyoming, and in the Dakotas. In Montana, the limestone beds are from 1,000 to 2,000 feet thick in places. Because Madison Limestone resists weathering and erosion much better than most other kinds of rocks, it forms many of the spectacular cliffs and dramatic ridges that make Montana such a scenic place to drive through. A magnificent outcrop of Madison Limestone is visible on the north side of Interstate 90 just a few miles east of this rest area. The limestone pinnacles were exposed when the soil around them eroded away, creating the dramatic canyon along the Clark Fork River. The red streaks visible on the rocks and soil is iron oxide.

About 75 million years ago molten rock intruded the area near the crest of the Garnet Range, seven miles north of this rest area. Northwest-trending faults and rock layers channeled mineral-rich fluids from the intrusion into Cambrian and Precambrian rocks to form three principal gold veins and numerous smaller, gold-bearing zones. Prospectors discovered gold placers at the mouth of Bear Gulch, about a mile northeast of the rest area in 1865; discoveries in other drainages of the Garnet Range soon followed. Although goldbearing veins were discovered by 1866, the technology was not readily available to work them. By 1896, however, numerous underground mines were producing gold, silver, and copper. In 1898, more than 1,000 people lived in the town of Garnet to support the miners living in the surrounding area.

11. The Anaconda-Pintler and Flint Creek Mountains

Montana Highway 1, MP 1, Anaconda rest area

GPS Latitude: 46.0942 Longitude: -112.8096

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The mountains surrounding this valley began to form more than 100 million years ago when tectonic forces compressed the earth’s crust and forced layers of underlying sedimentary rock eastward along great thrust faults. The faults stacked flat slices of rocks on top of one another to form high mountains similar to the Andes or Himalayas today. Molten rock was injected beneath the surface and cooled to form large masses of granite, called the Boulder Batholith, that are now exposed on the east side of the Deer Lodge Valley. Then, about 50 million years ago, the earth’s crust in this region began to be pulled apart. The crustal rocks were broken and the Anaconda-Pintler and Flint Creek Mountains to your west were separated from the Deer Lodge Valley by a gently east-sloping normal fault called the Anaconda detachment fault that forms the gently sloping mountain front on the west side of this valley.

Rocks that form the mountains are hard, resistant metamorphic and igneous rocks brought up from deep in the earth’s crust. The sedimentary rocks that formerly lay on top of those in the mountains slid eastward and downward along the detachment fault, and now lie buried beneath the Deer Lodge Valley. As the valley dropped and the mountains rose, the valley filled with thousands of feet of younger material derived from the eroding mountains. Although the Anaconda detachment fault is no longer active, other similar, but steeper, normal faults are, and so the mountains may still be growing.

12. The Boulder Batholith and the Richest Hill on Earth

I-15, MP 130 (south-bound)

GPS Latitude: 45.9911 Longitude: -112.4752

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The Boulder Batholith originated as part of the Elkhorn Mountains Volcanics. Molten magma rose up through the earth’s crust from 81 to about 74 million years ago. When it reached the surface, the magma created violent explosions that hurled chunks of rock, cinders, and volcanic ash into the air. The volcanic field was enormous–about 100 miles in diameter and up to 3 miles thick. After the pile of volcanic rocks got too thick, magma stopped going all the way to the surface and accumulated near the bottom of the pile. So much magma intruded at this level that when it cooled it formed a body of granitic rock, called a batholith. Granite similar to that exposed along Interstate Highway 15 north and east of Butte is the host rock for the ores mined at Butte. This granite formed by slow cooling of molten rock deep below the earth’s surface about 76 million years ago. Faults and fractures in the Butte area later cut the granite, forming pathways for hot water that carried metals in solution. As these solutions reacted with the enclosing granite they cooled and deposited quartz and metallic minerals to form veins. Some of these veins were of tremendous size: up to 50 feet wide and 4,500 long. The discovery of copper-rich veins together with the need for copper wire for electrical use from 1880 on stimulated both the development of many underground mines and the city of Butte. From a few dozen gold prospectors in 1864, Butte went to a reported population of 91,000 in 1917. The head frames of some of the former underground shaft mines can be seen piercing the skyline above the tan rock exposed on the sides of the Berkeley pit. Open-pit mining began there in 1955 and continued until mid-1982. Currently copper and molybdenum ore are mined in the Continental pit, which is hidden by the hills just west of the Interstate Highway.

13. Beaverhead Rock

Montana Highway 41, MP 13

GPS Latitude: 45.3657 Longitude: -112.4738

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The prominent geological feature to the west is called Beaverhead Rock. On the afternoon of August 8, 1805, members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition pulled its canoes up the Beaverhead River toward the Continental Divide. They sighted what Clark later called a "remarkable Clift" to the southwest. Sacajawea recognized this large promontory and told the captains that her people called it "beaver’s head." Beaverhead Rock is composed principally of Madison Limestone. About 350 million years ago, a shallow sea covered much of Montana. Billions of tiny marine creatures thrived in the water and when they died their bodies settled into the muck on the sea bed. After about 10 million years of accumulation and many more millions of years of compaction this muck became the pale gray rocks that are known today as Madison Limestone.

The prominent geological feature to the west is called Beaverhead Rock. On the afternoon of August 8, 1805, members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition pulled its canoes up the Beaverhead River toward the Continental Divide. They sighted what Clark later called a "remarkable Clift" to the southwest. Sacajawea recognized this large promontory and told the captains that her people called it "beaver’s head." Beaverhead Rock is composed principally of Madison Limestone. About 350 million years ago, a shallow sea covered much of Montana. Billions of tiny marine creatures thrived in the water and when they died their bodies settled into the muck on the sea bed. After about 10 million years of accumulation and many more millions of years of compaction this muck became the pale gray rocks that are known today as Madison Limestone.

The limestone is common throughout Montana, eastern Idaho, northern Wyoming, and in the Dakotas. In Montana, the limestone beds range from 1,000 to 2,000 feet thick. Because in Montana’s dry climate Madison Limestone resists weathering and erosion much better than most other kinds of rocks, it forms many of the spectacular cliffs and ridges that make Montana so scenic. Beaverhead Rock served as an important landmark not only for Lewis and Clark, but also for the trappers, miners, and traders who followed them into this area. It was known to many of them as Point of Rocks. In 1863, a man named Goetschius built a stage station on the "well-traveled, deep rutted road" between Bannack and Alder Gulch near here. It was part of the Montana-Utah Road, but was also known as Road Agents Trail because of all the robberies that occurred along it during the 1860s. In addition to changing tired horses for fresh animals for the stagecoaches, the station also served meals and provided a place to sleep for stagecoach travelers.

14. Earthquakes!

US Highway 287, MP 1

GPS Latitude: 44.8279 Longitude: -111.4677

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Few natural events cause as much fear in people as earthquakes. They remind us that the Earth is always changing and renewing itself and that this sometimes occurs violently and without warning. Earthquakes happen when stored energy is suddenly released by movement along a fault. A fault is a fracture that allows blocks of rocks to slide past each other. Tectonic forces gradually apply stress to the fault but friction along the fault keep the two sides locked in place. Eventually, the stress builds to the point where frictional forces locking the fault are exceeded and opposite sides of the fault suddenly slip past each other, releasing the stored energy. Some of this released energy radiates away from the fault surface as seismic waves, which we feel as an earthquake. The earthquakes in southwestern Montana are part of Intermountain Seismic Belt, a zone of frequent earthquake activity that extends about 800 miles from northwest Montana southward through Yellowstone National Park, through the Salt Lake City area, and all the way to southwestern Utah. A branch of the Intermountain Seismic Belt extends from Yellowstone about 300 miles west to the Idaho-Oregon border. The Intermountain Seismic Belt results from gradual stretching of the North American tectonic plate as it interacts with the Pacific tectonic plate. On August 17, 1959, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake struck Hebgen Lake about 12 miles northeast of here. The earthquake ruptured two faults, the Hebgen Lake fault and the Red Canyon fault, and caused parts of the Hebgen Lake basin to subside as much as 22 feet. The sudden tilting of Hebgen Lake caused a large wave—a seiche—to wash back and forth across the lake overtopping Hebgen Dam and sweeping shoreline cabins off their foundations. It also shook loose a mountainside—the 37 million cubic yard Madison Canyon landslide—that dammed the Madison River to form Earthquake Lake. The landslide buried part of a campground, killing 26 people.

15. The Shining Mountains

US Highway 287, MP 49, Lion's Park

GPS Latitude: 45.3487 Longitude: -111.7228

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The Madison Range rises from the east side of the Madison Valley along an active fault that threads its way along the base of the range. The mountains began to slowly rise along the fault about 50 million years ago and it remains active today. This was violently demonstrated on August 17, 1959 when a magnitude 7.5 earthquake struck the southern end of the Madison Range near Hebgen Lake. The earthquake triggered a massive landslide that dammed the Madison River, creating Earthquake Lake. Fault scarps as much as 21-feet high significantly changed the landscape and are visible in the valley along the length of the zone.

Several prominent peaks in the northern Madison Range, such as Lone, Pioneer, and Fan mountains, are supported by resistant igneous rock that developed from magma that pushed upward along layers of sedimentary rock. Glaciers and landslides carved the peaks into the shapes we see today. Sphinx Mountain is topped by 3,000 feet of gravelly conglomerate rock. The gravels that became these conglomerates were eroded from surrounding highlands and were deposited in an ancient valley that now is part of the highest peaks. Mountain streams deposited the sediments into the Madison Valley creating alluvial fans, named because of their fan shapes as seen from above.

Several prominent peaks in the northern Madison Range, such as Lone, Pioneer, and Fan mountains, are supported by resistant igneous rock that developed from magma that pushed upward along layers of sedimentary rock. Glaciers and landslides carved the peaks into the shapes we see today. Sphinx Mountain is topped by 3,000 feet of gravelly conglomerate rock. The gravels that became these conglomerates were eroded from surrounding highlands and were deposited in an ancient valley that now is part of the highest peaks. Mountain streams deposited the sediments into the Madison Valley creating alluvial fans, named because of their fan shapes as seen from above.

A Brief History: The Madison Range provided a spectacular backdrop to one of the most thrilling periods in the history of the American West, the fur trade. Beginning in the 1830s, American fur trappers, sometimes called mountain men, caught beaver in streams emptying into the Madison River. The fur trade was a cutthroat business as the fur companies competed for a limited and rapidly dwindling resource. By the 1840s the Blackfeet and the beaver had all but disappeared from this area. The mountain men's legacy lives on in the names of many geographic features in the region.

16. A New World: Tertiary Mammals

Montana Highway 55, MP 7

GPS Latitude: 45.8123 Longitude: -112.1682

Between the time dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, and the beginning of the Ice Age, some 2 million years ago, is a time called the Age of Mammals. During this period of time the western third of Montana experienced a variety of geological activities, some of which raised mountains and lowered valleys. The valleys became the homes of a wide variety of interesting and bizarre animals. Many of these have since gone extinct or today live in much warmer climates. During the early part of this time period, about 35 million years ago, Montana was home to animals like the double-horned rhinoceros-like brontotheres, and primitive little three-toed horses, camels, and deer. In the later part of the time period, 20 million years ago, the valleys hosted bizarre-looking ancestors of our modern elephants, camels, deer, and pigs. These included elephants with shovel-like tusks, deer-like animals with forked horns over their noses, and pigs the size of hippos. Montana was lush and subtropical. The extinction of these groups of animals would coincide with the coming of the Ice Age, and the arrival of humans less than 50,000 years ago.

Between the time dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, and the beginning of the Ice Age, some 2 million years ago, is a time called the Age of Mammals. During this period of time the western third of Montana experienced a variety of geological activities, some of which raised mountains and lowered valleys. The valleys became the homes of a wide variety of interesting and bizarre animals. Many of these have since gone extinct or today live in much warmer climates. During the early part of this time period, about 35 million years ago, Montana was home to animals like the double-horned rhinoceros-like brontotheres, and primitive little three-toed horses, camels, and deer. In the later part of the time period, 20 million years ago, the valleys hosted bizarre-looking ancestors of our modern elephants, camels, deer, and pigs. These included elephants with shovel-like tusks, deer-like animals with forked horns over their noses, and pigs the size of hippos. Montana was lush and subtropical. The extinction of these groups of animals would coincide with the coming of the Ice Age, and the arrival of humans less than 50,000 years ago.

17. A Passage Through Time: The Jefferson River Canyon

Montana Highway 2, Lewis and Clark Caverns State Park Group Use Center

GPS Latitude: 45.8238 Longitude: -111.8585

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The four-mile long Jefferson River Canyon was cut into the Tobacco Root Mountains between LaHood Park and Lewis and Clark Caverns State Park relatively recently in geologic time. The canyon exposes rocks that span over a billion years of geologic history. The rocks indicate times when the area was covered by shallow seas in which fine-grained sediment was deposited, and other times when rocks were exposed and eroded. The rocks also record times of volcanic activity and when stresses in the earth caused rocks to contort into folds or break into complex and significant faults. Entering the canyon from the east will take you backward in time. Most of the rocks at the east end of the canyon are sedimentary and volcanic rocks from the age of dinosaurs and younger. Gray cliffs of Madison limestone mark the entrance to the canyon, and form its walls for about a mile and a half to the west. Lewis and Clark Caverns developed in this limestone. A short distance beyond a northward bend in the highway, a steeper canyon is developed in dark-colored rocks of the La- Hood Formation that are much older than a billion years. In the outcrops of the LaHood Formation, chunks of a lighter-colored rock as much as 100-feet long are apparent within the dark rock of the canyon walls. They are boulders that broke off an ancient cliff produced by a major fault.

A Brief History: After much political wrangling and public comments by citizens in Three Forks and Whitehall, the Montana Department of Transportation rerouted US Highway 10 through the Jefferson Canyon in 1928. Prior to that, the old highway bypassed the canyon. The new road was difficult to build and engineers used dynamite to blast a route for it through the rocks. When completed in 1930, the highway was one of the most scenic routes in Montana. Bypassed by Interstate 90 in 1968, this highway still retains many of the design features common to Great Depression-era roads and is a unique driving experience.

18. Elkhorn Volcanoes and the Boulder Batholith

I-15, MP 177 (north-bound)/MP 178 (south-bound), Jefferson City rest area

GPS Latitude: 46.4066 Longitude: -112.0130 (north-bound)

Latitude: 46.4158 Longitude: -112.0060 (south-bound)

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The story of the Elkhorn Mountains Volcanics and the Boulder Batholith is the story of how molten magma or melted rock rising up through the crust of the earth just kept coming and coming and coming—from about 81 to about 74 million years ago. Magma that reached the surface created violent explosions, hurling chunks of rock, cinders, and volcanic ash into the air. At times it "rained" droplets of melted rock. Great clouds of volcanic ash were carried by the wind to the east and buried many animals. The dinosaur fossils in the Two Medicine Formation near Choteau owe their preservation to eruptions of the Elkhorn Mountains Volcanics. The volcanic field was enormous-about 100 miles in diameter and up to 3 miles thick. After the pile of volcanic rocks got so thick, magma stopped going all the way to the surface and just accumulated near the bottom of the pile. So much magma intruded at this level that it formed a body of granitic rock that now extends from Helena to Butte and is known as the Boulder Batholith. You are now in the middle of the Boulder Batholith and the Elkhorn Mountains Volcanics.

The magma was generated because one of the tectonic plates under the Pacific Ocean was subducted under Western North America. Approximately 10,000 miles of the Farallon Plate moved under Montana. This is one of places where it was easy for magma to reach the surface.

The magma was generated because one of the tectonic plates under the Pacific Ocean was subducted under Western North America. Approximately 10,000 miles of the Farallon Plate moved under Montana. This is one of places where it was easy for magma to reach the surface.

A Brief History: The magma contained many metals. As the granite formed cooling cracks, hot solutions squirted into the cracks to form veins with copper (near Butte) and gold (in this area). Millions of years later weathering of the granite allowed gold in the veins to wash down to the gravels in the valley floor. A gold dredge chewed through the gravels of Prickly Pear Creek beginning in 1938. Mounted on a barge floating on a 30-foot deep pond, the machinery consisted of a chain of buckets that dumped the gravel on a maze of screens and sluices inside the dredge. In its wake, the dredge left behind a "churned up" landscape. In some places scrub brush holding the gravel piles together is still the only vegetation. Although the dredge shut down permanently in the mid-1960's, it was not until the early 1970's that a South American mining company purchased it and moved it to Bolivia.

19. A Perfect Defile: The Prickly Pear Canyon

I-15, MP 222 • GPS Latitude: 46.9533 Longitude: -112.1080 (north-bound)

Latitude: 46.9544 Longitude: -112.1074 (south-bound)

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Here nestled deep in the Big Belt Mountains, is one of the most spectacular canyons in Montana. More than a billion years ago, during the Precambrian Era, an ancient inland seaway deposited these shales and sands, which over time, became these vibrant red and green mudstones called "Spokane Shale" for the Spokane Hills east of Helena. The Big Belts themselves consist primarily of Spokane Shale. They contrast with the magnificent white cliffs of Madison Limestone exposed in the nearby Gates of the Mountains and the drab gravels of Confederate Gulch to the southeast. The greenish colors in the mudstones are provided by tiny amounts of iron minerals that formed on mudflats that were low in oxygen; the intervening pinkish layers oxidized in contact with slightly greater amounts of oxygen.

Like most sedimentary rocks, there were originally laid down as horizontal layers. About 70 million years ago these rocks were crumpled, folded, and faulted during formation of the Rocky Mountains. As the floor of the Pacific Ocean slowly collided with the western margin of North America the horizontal layers became bent, broken, and tilted as you see them now. The most pronounced crumpling is here in the "overthrust belt" near the eastern edge of the Rockies. The Precambrian sedimentary rocks thin eastward in this area where they overlie the hard granite-like "basement" rocks of the central part of the continent.

A Brief History: Although this multi-hued and rugged canyon was well-known to Native Americans for thousands of years, it was first recorded by road-builder John Mullan in 1859. He called this rocky canyon "a perfect defile" and "by far the most difficult of any point along the [road], from Hell's Gate to Fort Benton." In 1865, the Territorial Legislature granted a license to the Little Prickly Pear Wagon Road Company to build a toll road through the canyon. A year later, in 1866, Helena merchants James King and Warren Gillette bought the road and spent $40,000 upgrading it. By then traffic on it between Fort Benton and Helena had become so heavy, that the men were able to recoup their expenditure within two years. By the early 1870s, it was part of the Benton Road, an important freight and passenger route in the territory. Thereafter, other roads and a railroad were constructed through the Prickly Pear Canyon, culminating in the completion of Interstate 15 in 1967. Montana's first Interstate rest area, here at Lyons' Creek, was built in 1965.

20. Cliffs High and Steep: The Adel Mountains Volcanics

I-15, MP 239, Dearborn rest area

GPS Latitude: 47.1311 Longitude: -111.9008 (north-bound)

Latitude: 47.1326 Longitude: -111.9016 (south-bound)

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through this canyon of "nearly perpendicular rocks" during its journey up the Missouri River in July 1805. Although the men grumbled about mosquitoes and prickly pear cactus, the Corps of Discovery was clearly impressed by the Adel Mountain Volcanics, the eroded remains of a pile of volcanic rocks more than 40 miles long and 20 miles wide. The volcanics consist mostly of fragments—blocks, cinders, ash—from violent, explosive eruptions that blasted magma out of the earth and into the air. The eruptions occurred about 75 million years ago and continued for several million years.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through this canyon of "nearly perpendicular rocks" during its journey up the Missouri River in July 1805. Although the men grumbled about mosquitoes and prickly pear cactus, the Corps of Discovery was clearly impressed by the Adel Mountain Volcanics, the eroded remains of a pile of volcanic rocks more than 40 miles long and 20 miles wide. The volcanics consist mostly of fragments—blocks, cinders, ash—from violent, explosive eruptions that blasted magma out of the earth and into the air. The eruptions occurred about 75 million years ago and continued for several million years.

Erosion has exposed some of the underground "plumbing" for the volcanic center. Magma rose up along cracks and had enough pressure to push the walls of cracks apart for tens of feet, forming dikes. At several places in the canyon, you'll notice the dark ridges— dikes—going up the mountainsides. Some magma squirted in along the bottom of the pile of volcanics forming horizontal intrusions called laccoliths. Square Butte, Shaw Butte, and Cascade Butte are prominent laccoliths with high, vertical cliffs that can be seen between Ulm and Cascade. This great eruption of magma occurred on the Great Falls Tectonic Zone—a collision zone between two continental plates which collided more than a billion years ago. It left a zone of weakness that resulted in the Adel Mountain Volcanics.

A Brief History: Native Americans frequently camped in this area on their way to and from the buffalo hunting grounds. The rugged landscape, however, largely prevented the non-Indian settlement of the area until late in the 19th century. Montana's first modern road-builder, John Mullan, skirted the mountains for a route far to the northwest. The canyon's residents were mostly cattle ranchers who sold their animals in Helena or Great Falls. The arrival of the Montana Central Railroad in 1887 did much to open this region to settlement, but it was not until the early 1930s that a modern paved highway connected Helena and Great Falls through this area. U.S. Highway 91 wound its way along the Missouri River through the volcanic outcrops of the canyon, crossing the river over two large steel truss bridges that still carry traffic in the vicinity of Hardy and Wolf Creek. Though bypassed by Interstate 15 in the 1960s, old U.S. 91 provides motorists a unique opportunity to experience a Great Depression era road through one of the most spectacular landscapes in Montana.

21. Egg Mountain

US Highway 287, MP 58 •

GPS Latitude: 47.7221 Longitude: -112.2319

In 1978, rock-shop owner Marion Brandvold found a group of small bones that paleontologists Jack Horner and Bob Makela later identified as baby bones belonging to a new species of duck-billed dinosaur. Horner and Makela named this new species Maiasaura peeblesorum, the good mother reptile. The site where the Maiasaura bones were found was named Egg Mountain, and has since yielded the largest cache of dinosaur eggs, embryos, and baby skeletons found in the Western Hemisphere. The site has also yielded one of the largest concentrations of adult dinosaur skeletons found in the world. Paleontologists have interpreted this accumulation as a gigantic herd of Maiasaura that died in a catastrophic event, possibly resulting from a volcanic eruption or a hurricane. Besides Maiasaura, a little meat-eating dinosaur named Troodon also nested at the Egg Mountain site. Its eggs indicate that they were brooded similar to birds, by direct contact of the parent. About 76 million years ago, when Maiasaura and Troodon lived in this area, the Rocky Mountains were just beginning to form to the west, and a shallow ocean existed 300 miles to the east. The dinosaurs nested near lakes and streams on a fern covered coastal plain. Maiasaura is Montana's state fossil.

In 1978, rock-shop owner Marion Brandvold found a group of small bones that paleontologists Jack Horner and Bob Makela later identified as baby bones belonging to a new species of duck-billed dinosaur. Horner and Makela named this new species Maiasaura peeblesorum, the good mother reptile. The site where the Maiasaura bones were found was named Egg Mountain, and has since yielded the largest cache of dinosaur eggs, embryos, and baby skeletons found in the Western Hemisphere. The site has also yielded one of the largest concentrations of adult dinosaur skeletons found in the world. Paleontologists have interpreted this accumulation as a gigantic herd of Maiasaura that died in a catastrophic event, possibly resulting from a volcanic eruption or a hurricane. Besides Maiasaura, a little meat-eating dinosaur named Troodon also nested at the Egg Mountain site. Its eggs indicate that they were brooded similar to birds, by direct contact of the parent. About 76 million years ago, when Maiasaura and Troodon lived in this area, the Rocky Mountains were just beginning to form to the west, and a shallow ocean existed 300 miles to the east. The dinosaurs nested near lakes and streams on a fern covered coastal plain. Maiasaura is Montana's state fossil.

22. A Pleistocene Wonderland

US Highway 2, MP 321

GPS Latitude: 48.5124 Longitude: -110.9751

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Imagine you are a time traveler and have the opportunity to visit this area 25,000 years ago. You would recognize the Rocky Mountains to the west. The igneous and heavily glaciated Sweetgrass Hills loom on the horizon far to the north. The last of the great continental glaciers had retreated, leaving behind a hummocky grassland with ponds, swamps, and erratic boulders. The grasslands support an abundance of animal life, much of which would be recognizable as still inhabiting the northern Great Plains today. However, there would also be many animals that have long been extinct. Almost all of them would be much larger and adapted to a colder post-glacial climate.

Imagine you are a time traveler and have the opportunity to visit this area 25,000 years ago. You would recognize the Rocky Mountains to the west. The igneous and heavily glaciated Sweetgrass Hills loom on the horizon far to the north. The last of the great continental glaciers had retreated, leaving behind a hummocky grassland with ponds, swamps, and erratic boulders. The grasslands support an abundance of animal life, much of which would be recognizable as still inhabiting the northern Great Plains today. However, there would also be many animals that have long been extinct. Almost all of them would be much larger and adapted to a colder post-glacial climate.

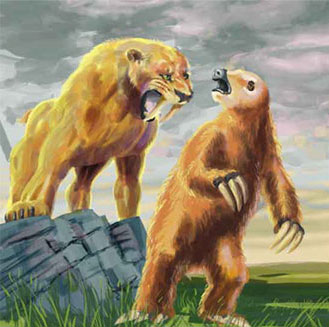

Great herds of horses, pronghorn antelope, elk, camels, and giant bison would be a common site on the plains. They milled around with groups of blond-haired Shasta ground sloths, and shaggy Musk and Shrub oxen. Columbian mammoths with long, curving tusks roamed the plains in small groups. Dire and Gray wolves and short-faced bears followed the herds in search of easy meals. At 10-feet in length and more than 2,000 pounds, the bears dwarfed today's Grizzlies in size and ferocity. Perhaps the most famous of all Pleistocene predators were the fearsome saber-toothed cats. Relatively small and compact, the cats may have ambushed their prey and slashed at them with their 7-inch long canine teeth. Perhaps even more deadly, however, was the long-legged American Lion, a killing machine bigger than the Bengal tiger. Climatic changes, limited food supplies, and, possibly, over-hunting by paleo-Indians caused many species once common to the northern Great Plains to become extinct about 11,000 years ago. The American bison, gray wolf, elk, and pronghorn antelope are descendants of that primeval ecology.

23. The Sweet Grass Hills

US Highway 2, MP 328

GPS Latitude: 48.5455 Longitude: -110.8558

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The three distinctive buttes on the horizon to the east are called collectively the Sweet Grass Hills. West Butte, the closest and highest, rises 3,000 feet above the plains. Middle Butte, farther in the distance and a little to the south, is grass covered and East Butte is the most distant. Together these three buttes make this range the most prominent in north central Montana. Like many of the mountain ranges on Montana’s great plains, the Sweet Grass Hills are the result of igneous activity about 50 million years ago when molten rock intruded Cretaceous sedimentary rocks. The surrounding sedimentary rocks were more rapidly eroded than the hard igneous rock leaving these three buttes and two much smaller buttes jutting up above the plains. At approximately the same time, similar igneous activity occurred in what are now the Highwood and Bears Paw Mountains and other mountains in central Montana. A continental glacier that flowed south from Canada covered this area with an estimated thickness of more than a 1,000 feet of ice, leaving the upper third of these buttes sticking up above the ice. Because the Sweet Grass Hills were not completely ice covered, they do not have the rugged sculpted appearance that characterizes many Montana mountain ranges.

Katoyisiks is the Blackfeet word for the Sweet Grass Hills and means "Sweet Pine Hills." Some of Blackfeet’s oldest stories and traditions involve the hills. According to Blackfeet tradition, Old Man made the Sweet Grass Hills with rocks he carried with him after creating the earth. Long ago the Blackfeet surrounded a party of Crow Indians on the Middle Butte. As night came and throughout the night, the Blackfeet pushed the Crow further up the hill. As this was occurring, the Crow would sing a particular song. With the first light of morning, the Blackfeet closed off their circle at the top. The Crow were gone. The Blackfeet still use this song in their ceremonies, such as the Sundance.

24. An Island on the Plains: The Bears Paw Mountains

US Highway 87, MP 79, Big Sandy City Park

GPS Latitude: 48.1748 Longitude: -110.1169

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Fifty-five to thirty-four million years ago, volcanoes erupted in several areas of central Montana. The upwelling of magma which fed these volcanoes was largely responsible for the Bears Paw Uplift and for several other isolated mountain ranges in central Montana. In some places, as the molten rock pushed its way upward toward the surface, it up-arched the layered rocks above it to form a magma dome called a laccolith. In other places, the magma rose vertically to form dikes. The dikes now look like old fallen-down stone walls protruding up through the grass of the ranchlands. Some of the magma crystallized into shonkinite, a rare rock, named for exposures near the town of Shonkin, Montana. Some of the laccoliths eroded to form large buttes, the most prominent are Square Butte northeast of Box Elder and Centennial Mountain northeast of Big Sandy. While the mountains were rising, an east-west rift developed near the crest, and rocks slid both to the north and south on Cretaceous marine shales. The sliding produced many faults in the adjacent Great Plains. The faults south of the mountains are especially prominent; while most of those to the north are covered by glacial deposits.

Fifty-five to thirty-four million years ago, volcanoes erupted in several areas of central Montana. The upwelling of magma which fed these volcanoes was largely responsible for the Bears Paw Uplift and for several other isolated mountain ranges in central Montana. In some places, as the molten rock pushed its way upward toward the surface, it up-arched the layered rocks above it to form a magma dome called a laccolith. In other places, the magma rose vertically to form dikes. The dikes now look like old fallen-down stone walls protruding up through the grass of the ranchlands. Some of the magma crystallized into shonkinite, a rare rock, named for exposures near the town of Shonkin, Montana. Some of the laccoliths eroded to form large buttes, the most prominent are Square Butte northeast of Box Elder and Centennial Mountain northeast of Big Sandy. While the mountains were rising, an east-west rift developed near the crest, and rocks slid both to the north and south on Cretaceous marine shales. The sliding produced many faults in the adjacent Great Plains. The faults south of the mountains are especially prominent; while most of those to the north are covered by glacial deposits.

A Brief History: It is not known how the mountain range got its name. According to one legend, many generations ago, an Indian man killed a deer while hunting in the mountains. Before he could return to his camp, he encountered a bear, which knocked him down and pinned him to the ground. The hunter appealed to the Great Spirit for help, who answered by filling the heavens with lightning and thunder, which killed the bear and severed its paw, releasing the hunter. Or perhaps one of the range's mountains resembles a bear's paw and gave the mountain range its name. Another tale states that to Indians looking down from the summit of one of the peaks, the ridges spread out below them resembled a bear's paw.

25. Mountains, Belt Butte and the Great Falls Coal Field

Montana 200/US 89, MP 71, Armington rest area

GPS Latitude: 47.3499 Longitude: -110.8960

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The scenic Highwood Mountains, visible on the skyline to the northeast, are composed of resistant volcanic rocks which tower above the relatively soft surrounding sedimentary rocks. The mountains contain an unusual abundance of a dark igneous rock called shonkinite. Shonkinite occurs in other parts of the world, but it was named for the exposures found near the community of Shonkin on the north side of the Highwood Mountains.

As you drive to the northwest, look for a prominent hill known as Belt Butte northeast of the highway. You can recognize it by its "belt" of Cretaceous sandstone. Belt Butte is notable because it gave its name to Belt Creek, the town of Belt, and to the Big and Little Belt mountains to the south. The Belt Supergroup, an extremely thick and extensive package of western Montana sedimentary and metamorphosed sedimentary rock, hundreds of millions of years old, is found in many mountain ranges of western Montana. The Supergroup was named for the Big and Little Belt mountains thanks to the "belt" of sandstone around Belt Butte!

The Little Belt Mountains, visible to the south, were bowed up by multiple blister-like pockets of magma, molten rock that arched up the overlying sedimentary layers to form domes. The domes and mountains are cored by igneous rock formed about the same time as the Highwood Mountains, about 50 million years ago.

The Great Falls coal field extends through the Armington area. The coal is discontinuous, having developed from plant material that accumulated in a number of Early Cretaceous swamps. Compaction of the remains of swamp plants over millions of years produced the medium-grade bituminous coal in the area. Coal mined in this area powered the locomotives of the Great Northern Railway, fueled the smelter at Great Falls, and heated homes throughout central Montana. Coal mining in the area declined after 1950, when the coal of the Great Falls field could not compete with diesel, oil, and natural gas.

26. The Little Rocky Mountains

Community Center, Lodgepole, Fort Belknap Reservation

GPS Latitude: 48.0342 Longitude: -108.5333

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The Little Rocky Mountains are an island on the northern Great Plains of Montana. About 50 million years ago, a fifteen-mile-wide igneous dome pushed its way up through 1700 million-year-old Precambrian basement rocks to form this spectacular mountain range. The mountains are a composite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks, Paleozoic limestone and dolomite, Mesozoic sandstone and shale, and Tertiary intrusive rocks. The loftiest portion of the range is girdled by a steeply dipping wall of Madison Limestone that makes the interior part of the range appear as a fortress. The Little Rockies also contain igneous dikes and sills that contribute to the rugged appearance of these mountains.

In 1884, prospectors found placer gold in many of the stream beds in the southern part of the range. The placers soon played out, and underground mining began. Hundreds of miners, most of whom lived in Landusky and Zortman, worked in mines that reached more than 600 feet deep to extract the gold and silver.

27. Bearpaw Shale and the Inland Seaway

Montana Highway 200, MP 158, Mosby rest area

Montana Highway 200, MP 158, Mosby rest area

GPS Latitude: 46.9945 Longitude: -107.8880

The black shale rocks seen in this area represent the muddy sediments deposited by the last ocean to exist in Montana. The shale, known by geologists as the Bearpaw Shale contains fossils of sea-going creatures that lived and died some 70 million years ago. Twenty foot long swimming reptiles like Mososaurus and Tylosaurus fed on fishes and ammonites, relatives of squids and octopi. The remains of the gigantic coiled ammonites called Placentaceras and the straight shelled ammonites called Baculites are often found in these shale deposits. This inland ocean extended north to south, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean, and divided North America into two subcontinents. Dinosaurs roamed the lands, and alligators and turtles inhabited the streams and rivers. But, one of the largest animals to live in this area was a gigantic, forty foot long crocodile called Deinosuchus that lived in the coastal waters of the inland seaway. The first remains of this animal were found near here. In the early 1900s, geologists learned that geological structures called anticlines, a kind of large wrinkle in the rock strata, were good places to drill for oil. Geologists also realized that certain parts of anticlines were better than others, and that the good spots were beneath structures they called domes. Here at the Mosby rest area you are standing on a part of the Mosby Dome, of the Cat Creek Anticline.

28. The Judith River Formation

Montana Secondary 236, MP 47

GPS Latitude: 47.7359 Longitude: -109.6269

In 1855, geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden explored the upper Missouri River for the United States Geological Service. At that time, the area was the hunting ground of the Lakota, Blackfeet, Atsina, and River Crow Indians. A lone white man in Indian Country was often fair game to the tribes, but Hayden's passion for rocks and fossils earned him the name "He Who Picks Up Stones While Running" and a reputation for madness. The Indians left him alone. Hayden explored what would later become known as the Judith River Formation, a large area of sedimentary materials deposited in the lowland areas bordering the Colorado Sea during the Late Cretaceous Period 78 to 74 million years ago. During his exploration near the mouth of the Judith River, Hayden collected many fossilized teeth, bones, and shells from the Judith River Formation. He took them to anatomy Professor Joseph Leidy in Philadelphia for identification, who classified the teeth as belonging to a new species of hadrosaur. The teeth and bones were the first dinosaur fossils found in North America. Hayden's discovery drew paleontologists to Montana in search of dinosaur fossils and to the Judith River Formation making it a significant paleontological destination.

29. Square Butte and Shonkin Sag

Montana Highway 80, MP 28

GPS Latitude: 47.6106 Longitude: -110.2731

Between the communities of Square Butte and Geraldine, two prominent geologic features dominate the skyline. About 50 million years ago, the Highwood Mountains had a sizeable volcano that erupted a rare rock called shonkinite, a dark rock similar to basalt. About 75 million years ago, magma injected eastward between layers of sandstone laid down along the shores of a broad inland sea extending to the southeast. Locally, that magma bulged up to form a huge blister or "laccolith" that solidified to form the immense flat-topped Square Butte to the south. The vertical cracks that fed magma to the laccolith radiated out from the center of the volcano and are called dikes. Square Butte is one of many laccoliths scattered from the Adel Mountain Volcanics south of Great Falls to the Bears Paw Mountains near Havre.

Between the communities of Square Butte and Geraldine, two prominent geologic features dominate the skyline. About 50 million years ago, the Highwood Mountains had a sizeable volcano that erupted a rare rock called shonkinite, a dark rock similar to basalt. About 75 million years ago, magma injected eastward between layers of sandstone laid down along the shores of a broad inland sea extending to the southeast. Locally, that magma bulged up to form a huge blister or "laccolith" that solidified to form the immense flat-topped Square Butte to the south. The vertical cracks that fed magma to the laccolith radiated out from the center of the volcano and are called dikes. Square Butte is one of many laccoliths scattered from the Adel Mountain Volcanics south of Great Falls to the Bears Paw Mountains near Havre.

During the Bull Lake Ice Age between 70,000 and 130,000 years ago, the continental ice sheet spreading south from Canada blocked the Missouri River, backing up its water to form Glacial Lake Great Falls. The glacial meltwater poured eastward through the Highwoods to erode Shonkin Sag, the large valley extending west, north of Square Butte. Shonkin Sag is one of the most famous abandoned meltwater channels in the world. (photo credit: Tim Urbaniak)

30. Paleocene Mammals and Albert Silberling

US Highway 12, MP 95

GPS Latitude: 46.4463 Longitude: -109.9386

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The town of Harlowton is located in the Fort Union Geological Formation, which was created about 65 million years ago, shortly after the dinosaur extinction. This once shallow inland sea was formed from rivers originating in the southwestern mountain slopes of Montana. These rivers transferred and deposited sediment collected from the swampy, subtropical eastern coastal plains into the shallow sea. As the rivers shifted over time, swamp vegetation and peat were covered with thick deposits of sand, silt, and clay, which would later form coal. These deposits cemented and compacted into sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone—soft materials that easily erode—leaving few outcrops of more weather-resistant rocks.

The area surrounding Harlowton is also famous for its Paleocene fossils. In 1902, Princeton University paleontologist Earl Douglass and Albert Silberling, a local homesteader and self-taught paleontologist, discovered the fossil remains of primitive mammals in a quarry southwest of Harlowton. Paleontologists excavated that quarry and three others over the next four decades and these sites yielded the remains of at least 23 species, including a squirrel-like animal called Ptilodus, the most successful of all mammals.

The area surrounding Harlowton is also famous for its Paleocene fossils. In 1902, Princeton University paleontologist Earl Douglass and Albert Silberling, a local homesteader and self-taught paleontologist, discovered the fossil remains of primitive mammals in a quarry southwest of Harlowton. Paleontologists excavated that quarry and three others over the next four decades and these sites yielded the remains of at least 23 species, including a squirrel-like animal called Ptilodus, the most successful of all mammals.

Ptilodus first appeared during the middle Jurassic Age about 160 million years ago and became extinct about 35 million years ago. It coexisted with massive sauropods, such as the Apatosaurus and Diplodocus, as well as the meat-eating Allosaurus. During Paleozoic time, Montana’s climate was warm, humid, and possibly densely forested. With its dexterous feet, legs, and tail, Ptilodus was a good climber with a well-developed sense of smell. Teeth recovered in the quarries indicate that it was herbivorous. Other fossils found by Douglass and Silberling include a primitive species of ungulate called Phenacodus, and a primate-like animal called a Plesiadapis, all of which co-existed with the Ptilodus and were preyed upon by Creodonts, the dominant carnivorous animals of the time. Albert Silberling’s excavation of thousands of fossils and his discoveries from quarries in the Harlowton area have greatly contributed to scientists’ knowledge about life in the Paleozoic Era.

31. Surrounded by Mountains

Montana Highway 84, MP 27

GPS Latitude: 45.6711 Longitude: -111.2308

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The Gallatin Valley is one of the most picturesque and agriculturally productive valleys in Montana. From here, you can see four prominent Montana mountain ranges: the Bridger Range (east), Gallatin Range (south), Spanish Peaks (southwest), and the Big Belt Mountains (north). Each range has its own unique geology and topography.

The high peaks of the Gallatin Range are carved from volcanic rocks and volcanic-derived mudflows that erupted during the Eocene, approximately 45 million years ago. The Spanish Peaks expose metamorphic rocks that date back to the Earth’s early history, over 3 billion years ago. Ancient metamorphic rocks are also exposed in the Tobacco Root Mountains, with the added bonus of a much younger granitic pluton exposed in the center of the range. The Elkhorn Mountains are composed of a thick succession of volcanic rocks that erupted about 75 million years ago, during a time when Montana was experiencing extensive mountain building – the birth of the Rocky Mountains.

The uplift of the Rocky Mountains spanned tens of millions of years from the Cretaceous to the early Cenozoic and was driven by tectonic compressional forces along the western plate boundary of North America, affecting all of western North America from Alaska to Mexico. When mountain building ended around 50 million years ago, the landscape of southwest Montana did not look like the spectacular, snowcapped mountains we see today. Glaciers later carved the Rockies into the jagged peaks we see today. Over the last 50 million years, western Montana experienced several phases of regional extension and block-faulting, resulting in the creation of modern Basin-and-Range topography. The crest of the Bridger Range arch slowly down-dropped one earthquake at a time to form the modern Gallatin Valley. Thick layers of midand late Cenozoic sedimentary rocks and more recent stream deposits have been deposited in the Gallatin Valley, producing the fertile landscape that Native Americans called the "Valley of Flowers" – the Gallatin Valley.

32. Lone Mountain

US Highway 191, MP 47

GPS Latitude: 45.2638 Longitude: -111.2538

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

Geologic processes have created a winter wonderland for skiers and snow boarders on Lone Mountain, the prominent peak that rises above Big Sky. Some geologists think that if the mountain was cut in half, there would be a Christmas tree pattern of igneous rock within layers of sandstone and shale. Magma from deep in the earth rose up along a vertical crack, then spread out laterally between the layers of sedimentary rock. The magma never erupted as a volcano, but crystallized into an igneous rock called dacite before it reached the surface of the earth. The "trunk and branches of the tree" are dacite. The igneous rock and adjacent baked sedimentary rocks are much more resistant to erosion than softer sedimentary rock, which has eroded away to leave the mountain standing tall. Glaciers, landslides, and rock fall have greatly modified Lone Mountain, sculpting bowl-shaped cirques high on Lone Mountain. The cirques contain rock glaciers, which are piles of rock with year-round ice in their cores. Like ice glaciers, they slowly creep down the mountain slopes.

Geologic processes have created a winter wonderland for skiers and snow boarders on Lone Mountain, the prominent peak that rises above Big Sky. Some geologists think that if the mountain was cut in half, there would be a Christmas tree pattern of igneous rock within layers of sandstone and shale. Magma from deep in the earth rose up along a vertical crack, then spread out laterally between the layers of sedimentary rock. The magma never erupted as a volcano, but crystallized into an igneous rock called dacite before it reached the surface of the earth. The "trunk and branches of the tree" are dacite. The igneous rock and adjacent baked sedimentary rocks are much more resistant to erosion than softer sedimentary rock, which has eroded away to leave the mountain standing tall. Glaciers, landslides, and rock fall have greatly modified Lone Mountain, sculpting bowl-shaped cirques high on Lone Mountain. The cirques contain rock glaciers, which are piles of rock with year-round ice in their cores. Like ice glaciers, they slowly creep down the mountain slopes.

The rugged mountains to the northwest of Big Sky are the Spanish Peaks, composed of metamorphic rock that is billions of years older than the igneous and sedimentary rocks on Lone Mountain. These extremely old rocks were brought up from the depths along an enormous fault zone that extends from the Tobacco Root Mountains to the town of Gardiner north of Yellowstone Park.

A Brief History: The mountains provided a spectacular backdrop for visitors to one of the Gallatin Canyon's many dude ranches. The ranches offered visitors adventure and a taste of the Old West. They rode horses, hiked mountain trails, fished the area's trout streams, and reveled in the solitude of the mountains. The ranches were immensely popular before World War II, but their popularity diminished in the 1950s until now only a few remain.

33. Hepburn's Mesa

US Highway 89, MP 24, Emigrant rest area

GPS Latitude: 45.2950 Longitude: -110.8349

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The black-capped bluffs located on the east side of the Yellowstone River are called Hepburn's Mesa. The mesa is capped by a basalt lava flow that erupted from a small local volcanic vent that has long since eroded away. Geologically, the lava flow is very young, perhaps having erupted as recently as 2.2 million years ago. Large amounts of iron in the basalt make it dark colored. Some of the iron crystallized as the mineral magnetite, which as the name implies is magnetic, and in large concentrations can cause compasses to behave erratically. The basalt flow overlies unconsolidated gravels, which in turn overlie older light-colored fine-grained sedimentary rocks that were deposited in an ancient lake that once occupied this site. The sedimentary beds of Hepburn's Mesa contain abundant Miocene fossils, including ancient rodents, moles, and a proto-horse called Merychippus, the first equine to exhibit the distinctive head of today's horses. On top of Hepburn's Mesa, overlying the basalt is glacial till of Pleistocene age. The surface of these deposits is hummocky and is littered with abundant glacial erratic boulders. For generations, Native Americans drove bison off the mesa's cliffs to obtain food, hides, and other materials important to their way of life.

The black-capped bluffs located on the east side of the Yellowstone River are called Hepburn's Mesa. The mesa is capped by a basalt lava flow that erupted from a small local volcanic vent that has long since eroded away. Geologically, the lava flow is very young, perhaps having erupted as recently as 2.2 million years ago. Large amounts of iron in the basalt make it dark colored. Some of the iron crystallized as the mineral magnetite, which as the name implies is magnetic, and in large concentrations can cause compasses to behave erratically. The basalt flow overlies unconsolidated gravels, which in turn overlie older light-colored fine-grained sedimentary rocks that were deposited in an ancient lake that once occupied this site. The sedimentary beds of Hepburn's Mesa contain abundant Miocene fossils, including ancient rodents, moles, and a proto-horse called Merychippus, the first equine to exhibit the distinctive head of today's horses. On top of Hepburn's Mesa, overlying the basalt is glacial till of Pleistocene age. The surface of these deposits is hummocky and is littered with abundant glacial erratic boulders. For generations, Native Americans drove bison off the mesa's cliffs to obtain food, hides, and other materials important to their way of life.

A Brief History: Hepburn's Mesa is named for John Hepburn, a local rancher, rockhound and amateur paleontologist. He arrived in the Emigrant area in 1909 after working in Yellowstone National Park for many years. From 1935 until his death in 1959, he operated a museum next to Secondary Highway 540 that displayed many of the geologic specimens and fossils he had found in this area. The museum was a local landmark for many years. It still stands next to the old highway and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

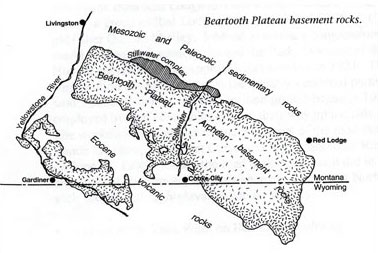

34. The Beartooth Plateau

US Highway 212, MP 69

GPS Latitude: 45.1776 Longitude: -109.2476

View/Download a PDF of the Road Sign

The Beartooth Plateau contains some of the oldest exposed rocks on Earth and provides a unique window into the history of our planet. About 55 million years ago, this massive block of metamorphic basement rock pushed its way upward nearly two miles along steep faults that extend deep into the Earth. The exposed rock consists of coarse-grained gray and pink granites, gneisses, and schists that formed about 3.3 billion years ago when older sedimentary and volcanic rocks were heated and recrystallized deep in the Earth at extremely high temperatures. The plateau contains the oldest exposed rocks in Montana and they are among the oldest on Earth. The Stillwater Complex on the plateau's northern flank is one of the world's major sources of chromite, platinum, and palladium.

During the ice ages, about 100,000 years ago, the Beartooth Plateau collected enough snow for glaciers to form and cover most of the plateau to a depth of several thousand feet. The spreading glaciers wore down the plateau's upper surface to leave the distinctively rounded rock outcrops, along with hundreds of lakes, ponds, and depressions. They flowed down old stream valleys, leaving them deepened and straightened, with vertical canyon walls and jagged peaks. The summit of the plateau is alpine tundra.